Europe’s Leading

Cookieless Marketing Data Platform

500+ leading companies are using Commanders Act Platform X to collect, analyse and activate marketing data with the goal of optimizing business growth.

Improved Data

Collection

Cross Device

Matching

Ad Return

on Investment

JOIN THE 500+ COMPANIES USING OUR PLATFORM

A single enterprise-grade platform to drive business growth

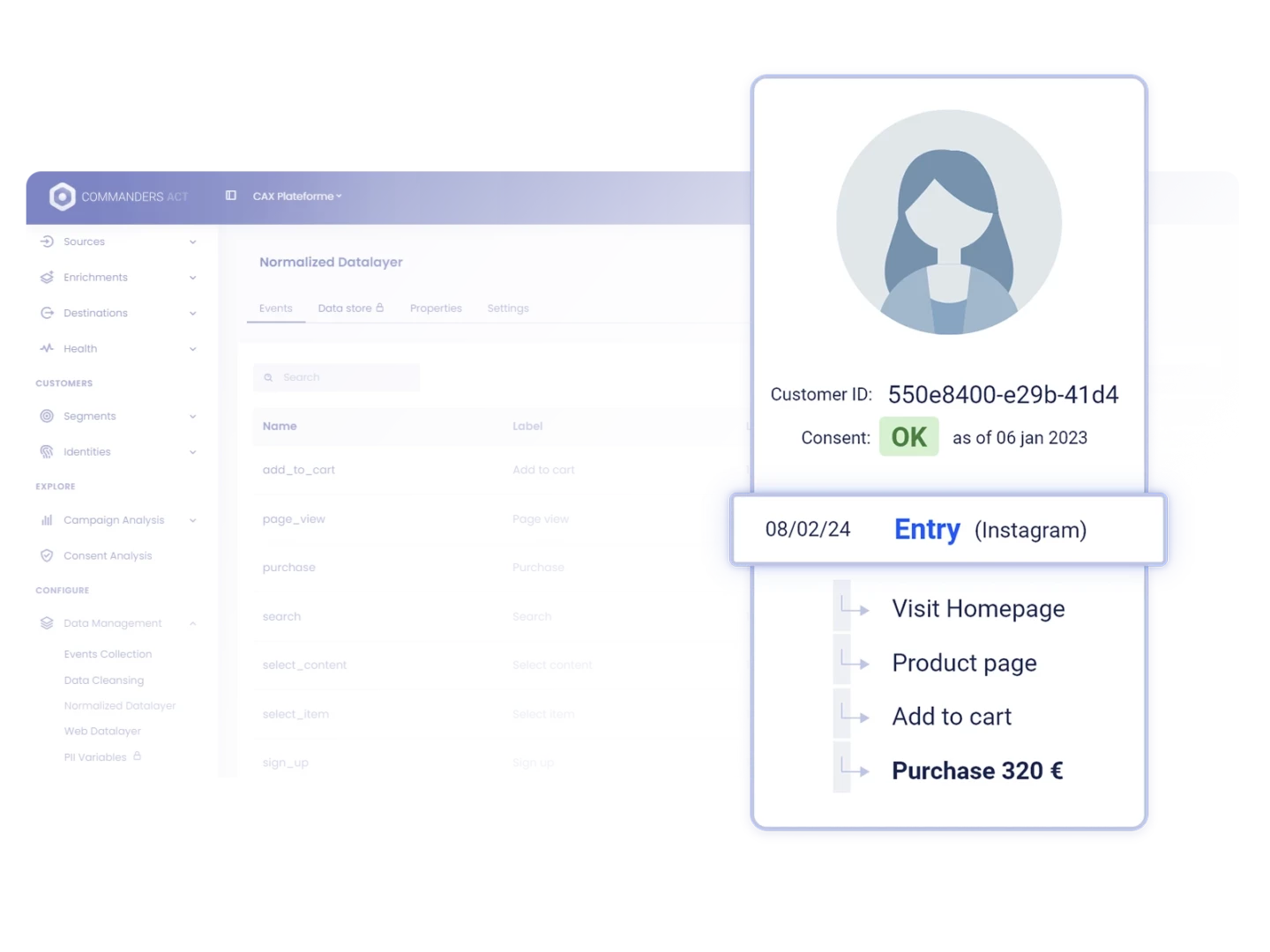

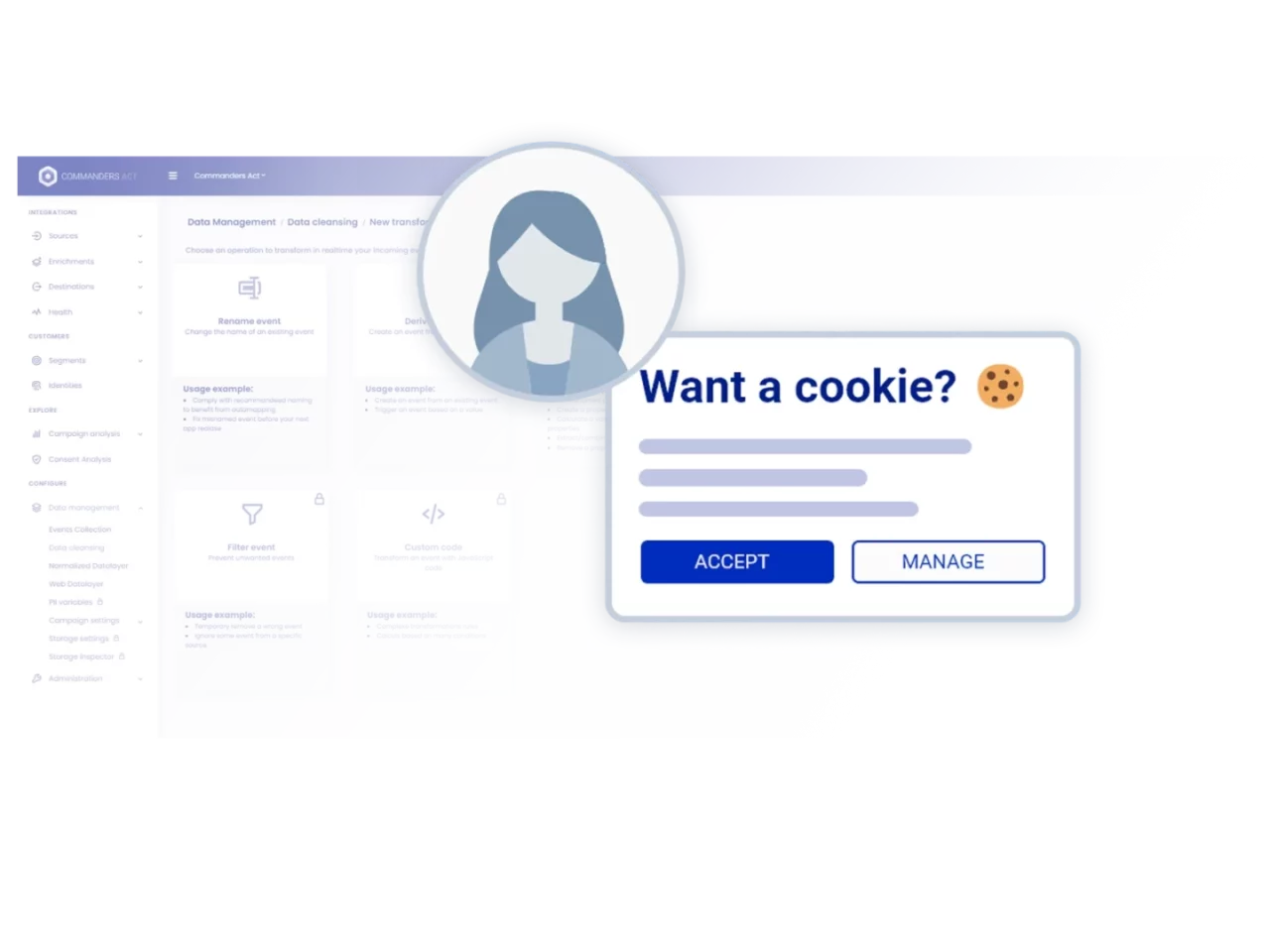

Trusted customer data fuels better experiences

and increases ad budget efficiency

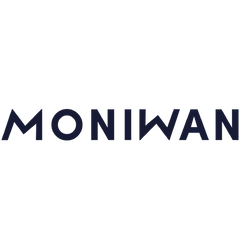

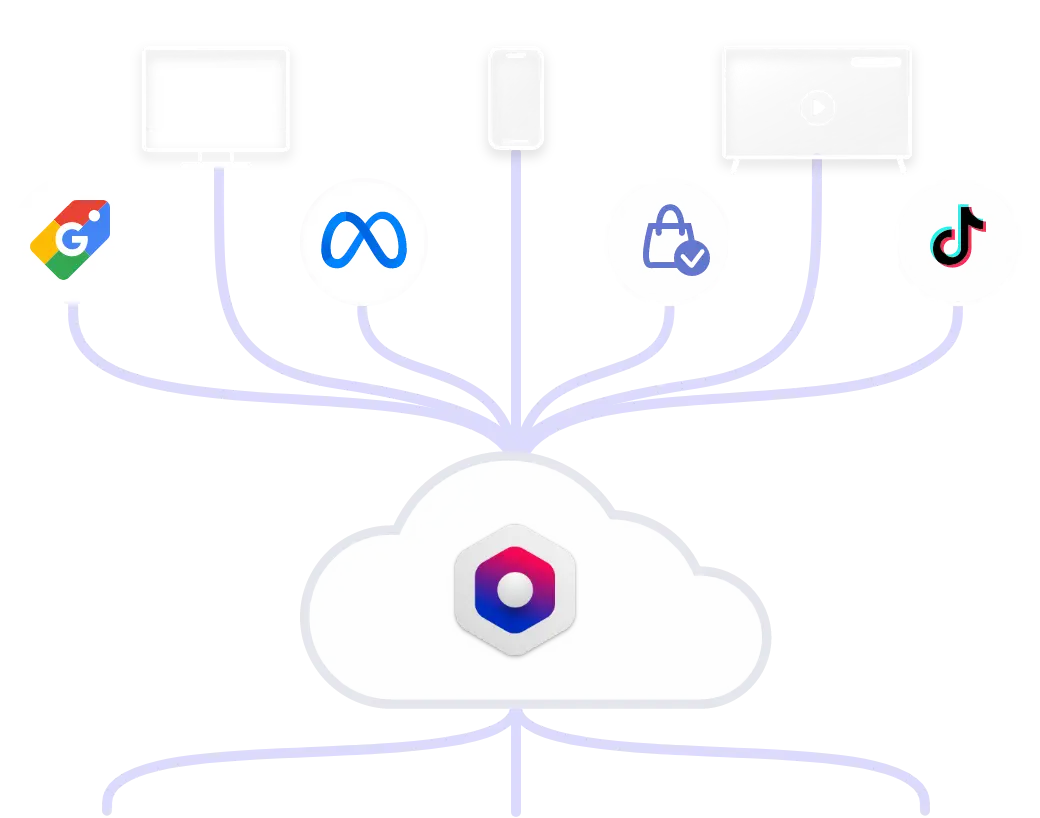

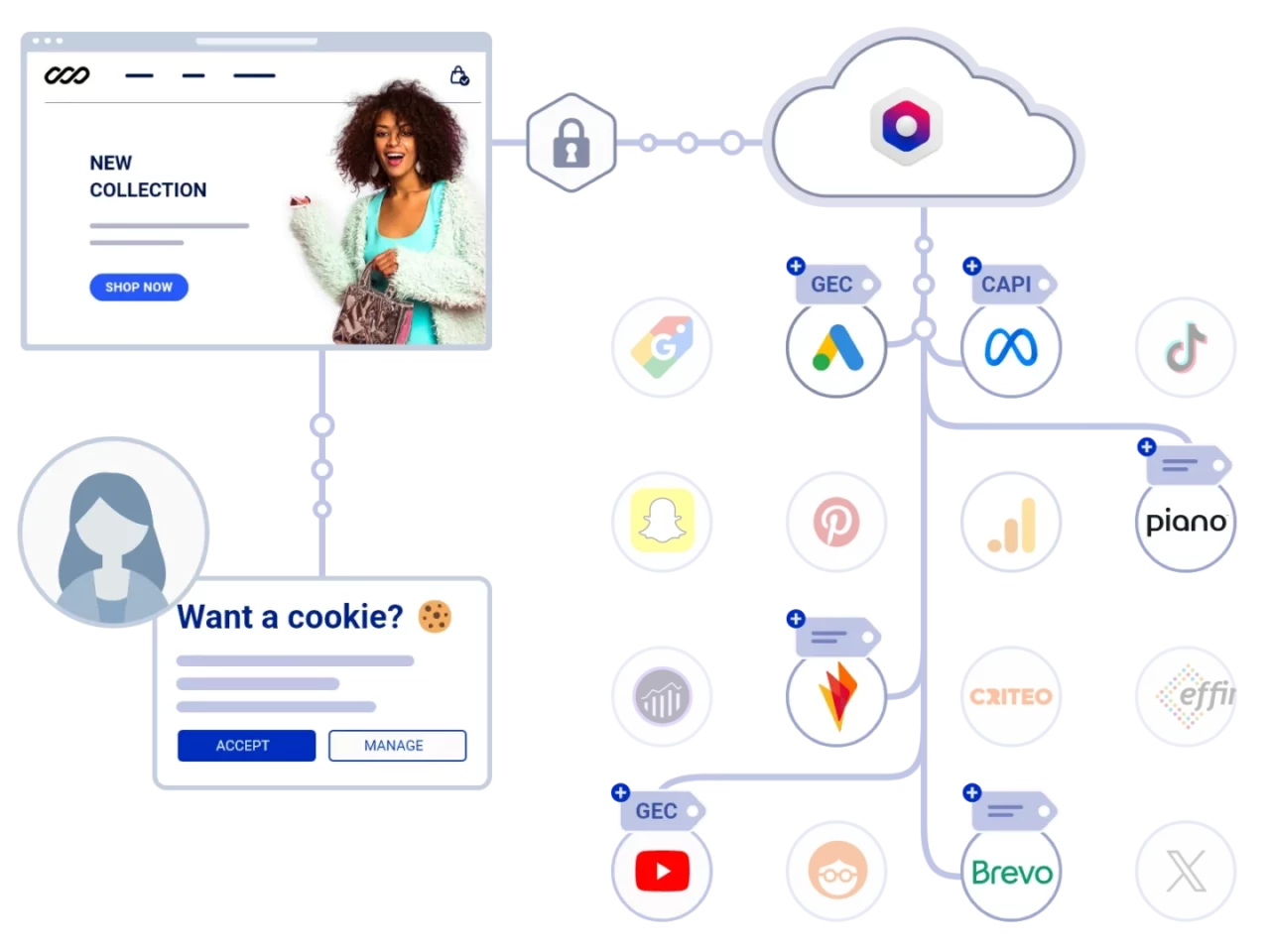

Trusted Data Collection & Delivery

Collect customer data in a privacy-compliant cookieless environment using our Client- & Server-side 1st-party tracking beacons.

Cookie KeEper

GTM-READY server side INTEGRATION

ACTIVATE GEC & CAPIS

COLLECT, OPTIMIZE, ACTIVATE

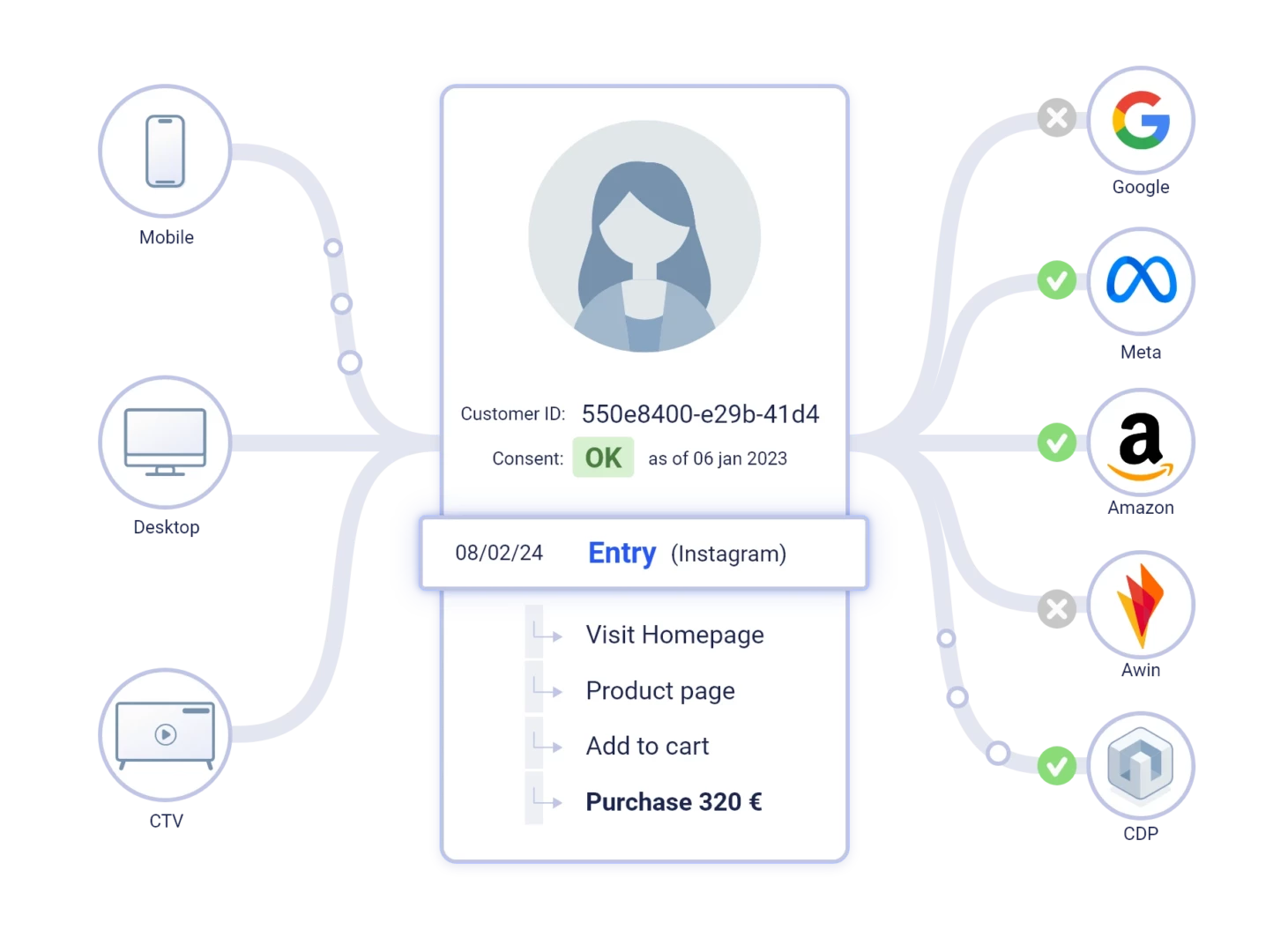

Leverage Trusted, Compliant Data to Increase Customer Activations & ROI

Trusted First-Party Data Collection

Ad Budget Optimization

Customer Profiling & Activation

1200+ Connectors

Let Your Data

Tell a Better Story

Trusted By